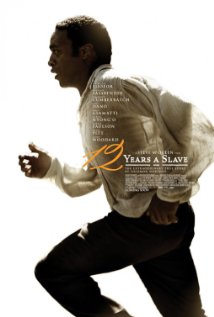

Drama, 134 Minutes, 2013

Slavery was a reality in the United States for the first 89 years of its existence and in the colonies for 157 years before that. It was abolished only 149 years ago. It’s impossible to underestimate the devastating impact this had, and continues to have, on this country.

It’s often forgotten that for several decades in the antebellum United States slavery had been slowly, but surely, eradicated in the North but was legal and highly institutionalized in the South. As the importation of slaves had been banned in 1808 there was, for a time, a lucrative business in kidnapping free black men and women and selling them south. Thousands of lives were ruined and families destroyed.

Solomon Northup (played by Chiwetel Ejiofor [IMDB]) was one of these unfortunate souls. In 1841 he is engaged as a violinist for a tour ending in Washington D.C. where he is apparently drugged. He wakes up chained and is tortured into accepting his position as a slave being shipped to Louisiana. Once there , a new identity is forced upon him and his hopes of freedom dwindle.

The film tells his incredible story with a subdued, sustained melancholy. Solomon struggles to maintain both hope and dignity while being crushed by the relentless, oppressive truth of his circumstances. He is first sold to a kindly, “model” master (Benedict Cumberbatch [IMDB]) that values and appreciates his intelligence and contributions. However, an incident with one of his handlers threatens his life and he’s sold to another (Michael Fassbender [IMDB]), less considerate, master.

The film doesn’t pull any punches, nor should it. The cruelty and inhumanity of his abductors. The flayed, bleeding capitalism of the slave broker’s parlor. The mercurial nature of the slave master and his often petty torments. The tedium of life when you’re forbidden from reading or writing and must wait on the whims of others to move you. The cruel working conditions in the cotton fields.

Very little background music is used. This adds a sense of weight and immediacy to the the film. American audiences tend to rely too heavily on musical cues. Pavlovian responses are easy to generate but the emotions resulting from them can be shallow, rote. This film forces you to actively analyze and confront the events being witnessed.

There are missteps. The film didn’t, for example, provide a meaningful sense of the passage of time. This may have been purposeful, an attempt to demonstrate the timelessness of hopeless situations, but it may also unintentionally downplay the amount of time he was detained. There are also several instances where we see nothing but a close-up of a teary-eyed Chiwetel for an extended period. Again, this was clearly purposeful, perhaps to let the audience better internalize his pain, but they could border on artistically indulgent.

There’s no point in beating around the bush here: Chiwetel will win the acting Oscar for his performance. Detractors will likely imply that societal guilt over slavery will play a part in his win. It indeed plays a part, as will the Academy’s well-known affection of period dramas, but none of that should detract from his achievement as an actor. He strikes a rich, meaningful balance between the dignity and stature of a free, educated man and the poor, servile, beast-of-burden he must be to survive.

This is an important story; one I’m surprised it has taken this long for Hollywood to tell. It’s told with a grace and elegance that are sadly absent from other recent films. It refuses to take the easy path of spoon-feeding the audience anti-slavery pablum and forces them to truly consider the human cost inherent of institutionalized degradation.

The autobiography of Northrup (12 Years A Slave) wash turned into a TV movie in 1984 entitled Solomon Northrup’s Odyssey, later re-issued as Half Slave, Half Free.